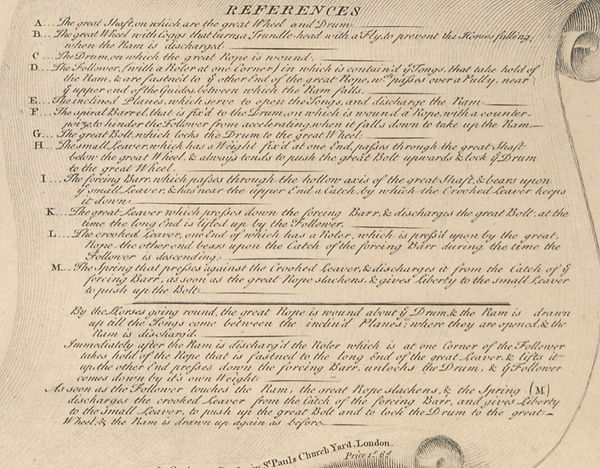

Months of research and study have gone into trying to get into the mind of the original maker and figure how the missing parts worked. Here is a sample of the written description from 1737, so the language is rather interesting. This is the text of parts G & H in Vauloue’s broadside. “G. The great bolt which locks the drum to the great wheel~ H. The small lever which has a weight fixed to at one end passes through the great shaft below the great wheel and which always tends to push the large bolt upwards, so as to lock the drum against the wheel~”

To this was added trade practices at the time, materials used along with making no modifications to the original. My work included making over 65 parts in steel and brass, most with non-standard thread sizes such as 1 1/2-56, 0.085”-60 and #8-30. Screw head pattern were copied from existing original screws and brackets riveted together as in other demonstration models in the King George III Collection. The “tongs” (part “D” in Vauloue’s broadside) were quite complex and clearly not understood by some of the other engravers. They are mounted in the “follower” which grabs the “ram” and lifts it to the top, releases it automatically, then goes down to get it again and repeats. The question is just what is the exact size of them. To figure that out I read all the descriptions of what it does, how and when it grabs and releases the “ram”. Then I cut out a pair in plastic to see if the geometry was correct, it wasn’t, so I redesigned and did it again. After getting it to function in plastic, I then cut out the parts in 1/16” steel. I use a jewelers saw for this, yes it takes a little time, in this case a little over an hour for these parts. The result is fairly complex shaped parts that would have taken quite a bit of time to mill out or program for CNC, which I do not use. Then the rollers and brackets were made and the whole tong assembly ended up having 22 parts in it.

A knob turns the mechanism to demonstrate the machines function. It was missing however part of the screw was broken off in the clock style brass flywheel. It took about an hour to drill it use an easy-out to get it out so I could measure the thread. Then I dropped it and spent the next 1/2 hour hunting it down through the cracks in my shops parquet floor. It measured .085 by 60 threads per inch and luckily I had and adjustable die for 3/32” (.093”) by 60, close enough. I made a steel, domed and slotted head shoulder screw. The knob was turned from Black wood.

There were a few wood parts missing, the originals were made of Cuban Mahogany which if you have ever worked with it you know what a wonderful wood it is. So desirable it was all used up and can no longer be sourced, especially the old growth stock. My stash of it has a great history. In 1957 Robert M. Vogel started work at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC., he retired 31 years later in 1988 as the Curator of Mechanical & Civil Engineering. In his first months of work at the museum they were doing renovations to original iconic Smithsonian Castle completed in 1855. They were tearing out the original display cases made of old Cuban Mahogany, these were in the grand 19th century style with carved Corinthian columns on the corners. They were being broken up and dumped out by the National Arboretum. After his work day, Robert would go out and dig through the pieces and retrieve the best which he stored in a rented garage. As I was designing and building Twin Manors I had envisioned a finely detailed wood base. Robert told me about these cases he saved, which he had not seen in decades and I agreed to buy them. In the mid 1980s he drug them out of storage and they were not as complete as he remembered. All that was salvageable were a couple of the fantastic columns that have hung in my shop for years and a few boards.

This mahogany has rich color and perfect grain match, so it is perfect for the replaced parts for the pile driver model. Just like the model, this wood has a history of its own.

The ladders are mortise and tenoned and made to fit so tight that they snap into place. I made them with a slight taper being wider at the bottom and on the upper ladder the top and bottom step are a different profile as James Ferguson did on his model now in the Science Museum London.

This gives a hint of the level of detailed work I put into this project. Most of the 100+ replacement parts I made were signed with my name or initials and in a few cases the date, 2022. This is so in the future it could be determined what is original and what is not. The parts were then aged, rusted and stained to match the finish on original model.

The builders and designers of these Pile Driver Models were brilliant and suburb craftsman! This has been one of the most fun and challenging projects I have done in quite some time. It was such a privilege to bring this back to life after 250+ years.

I am sure there are more of period models of Vauloue’s Pile Driver in other public or private collections. If you know of any or are researching these please contact me at robertsonminiatures@gmail.com

Other examples in museums, print and art

Vauloue’s Pile Driver 1737, model circa 1760

This 18th c. demonstration model of Vauloue’s Pile Driver has been added to the Wm. R. Robertson Collection after 35+ years of trying to own it. Mr. Robertson, a professional miniaturist and model maker for the last 46 years has spent months researching and restoring this to working condition. Each missing part made is based on other existing models, workshop practices of the period and is entirely removable with no damage done to the original model. This model is 20” high, 18” long and 7” wide.

First, what is a Vauloue Pile Driver? James Vauloue, a watchmaker by trade invented this pile driving machine in this in 1737. It featured a fusee mechanism, common in clocks and watches of the period to even out tension of the driving force, be it a spring or weights. On the pile driver that adjusted the tension of the ropes wrapped on the drum when it dropped. This in turn allowed the 3 horses powering it to not serge and fall from the uneven tension as the weight was released. This way the horses driving the machine could just be led around in a continuous circle allowing the machine to automatically lift the 1,000 pound weight known as a ram and drop it. It could do this 5 times in 2 minutes. This was one of the greatest advances in construction technology since the Renaissance. Before Vauloue’s invention a typical pile driver had 2 dozen or so ropes connected to the ram that men lifted and dropped together, then went and picked up the loose ends and did it again and again.

It was first used to build the original Westminster Bridge over the Thames River in London between 1738 and 1750. It was such a big deal that Vauloue was awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society with a prize of a £150. That would be something like $40,000 today or a couple thousands days wages working as a watchmaker.

Since this was the newest and greatest machine working on principles most people did not understand a number models were made, 8 of which are known in museums. They were used in lectures on Natural Philosophy, which is like Physics today, in the 18th century in London and other places of advanced learning. These demonstrations were given and published by leading learned men of the day such as James Ferguson and John Desaguliers. Also Stephen Demainbray, superintendent at the King’s Observatory at Kew and private tutor to King George III. Vauloue’s pile driver was also depicted in painting of the period. At the end of this story the known models, engravings and paintings are shown.

Model of Vauloue's Pile Driver after restoration by Wm. R. Robertson Aug. 2022 to Jan. 2023

Condition of Pile driver model before restoration, 20" H x 18" L x 7" W

How did I come by this? It was purchased by a friend at a yard sale in Old Town Alexandria, VA. about 4 decades ago for $1. He recently remembered it was in a row of boxes lined up on the ground and destined for the dumpster at the end of the sale. He noticed parts were missing and looked in through the other boxes to no avail. Just a little history here, in the Colonial period when this pile driver was created, there were two ports near the navigable end of the Potomac River, Alexandria on the Virginia side and Georgetown on the Maryland side. Later they built Washington, D.C. between them. The model appears to have been put away, in the dark since there is no sun damage, for a very long time. Assuming the model had been in the colonies the list of men who would have had an interest in the sort of thing from Virginia is rather short. Could have George Washington, Thomas Jefferson or George Wythe seen or even owned it?

At the time my friend bought this he did not know for sure what it was. When I first saw it in the early 1980s I knew immediately what it was and told him. How I knew that I’m not sure but it must stem from interest in all sorts of scale models since childhood. For years I tried to purchase or trade for it. In August of 2022 he gave it to me figuring I would be the best person to understand and restore it.

About half of the known (at least to me) models in museums are by scientific instrument makers, James Ferguson, Benjamin Cole, etc. The skill needed to make these models is extreme as the timbers on mine are planed to within just a few thousandths of inch of each other. The mortise and tenon joints are perfectly hand cut. Whomever made this was a very good at his trade and I suspect this would have been very expensive. I also wonder who, the workman at the bench, the prospective owner, or the master of the shop, studied and translated what is shown in the published engraving into working drawings? There are a lot of details that are not shown that one would need to know to build such a model. Or were there enough real full size machines the maker could just walk down to the river and look at one? One thing is for sure that each maker interpreted the drawing in their own way as no two models are alike.

Among the many interesting questions is do the other examples still work? Some clearly do not as museums tend not to play with objects as much as private collectors. Even from Vauloue’s written descriptions these are pretty tricky, add 250+ years of age, warping, missing parts and the task becomes even harder.